Heat waves keep breaking records, energy bills are rising, and technicians book out fast. Considering a ductless mini‑split but want control over cost, timing, and quality? Here’s a safe roadmap to installing a split air conditioner. You will see which tasks a careful DIYer can handle, when a licensed pro is the right (and often legally required) choice, and how to avoid the mistakes that cause leaks, poor performance, or voided warranties. Keep reading for clear steps, credible data, and practical tips that work worldwide.

What You Can (and Should Not) Do Yourself to Install a Split AC Safely

Most DIYers stumble by underestimating the scope. A split system looks simple—an indoor evaporator, an outdoor condenser, and two copper lines—but the details matter. Routing a condensate line with the correct slope, drilling a clean wall core, isolating vibration, sealing penetrations, and setting the outdoor unit on a solid base are all doable for a careful homeowner. Electrical and refrigerant work, however, is where projects often go wrong. In many countries, and in the United States under EPA Section 608, handling refrigerants requires certification. That means tasks like opening the sealed system, pulling a deep vacuum with a pump, charging refrigerant, or recovering it from old equipment must be done by a licensed HVAC technician. Attempting those steps without training risks injury, environmental harm, and equipment damage.

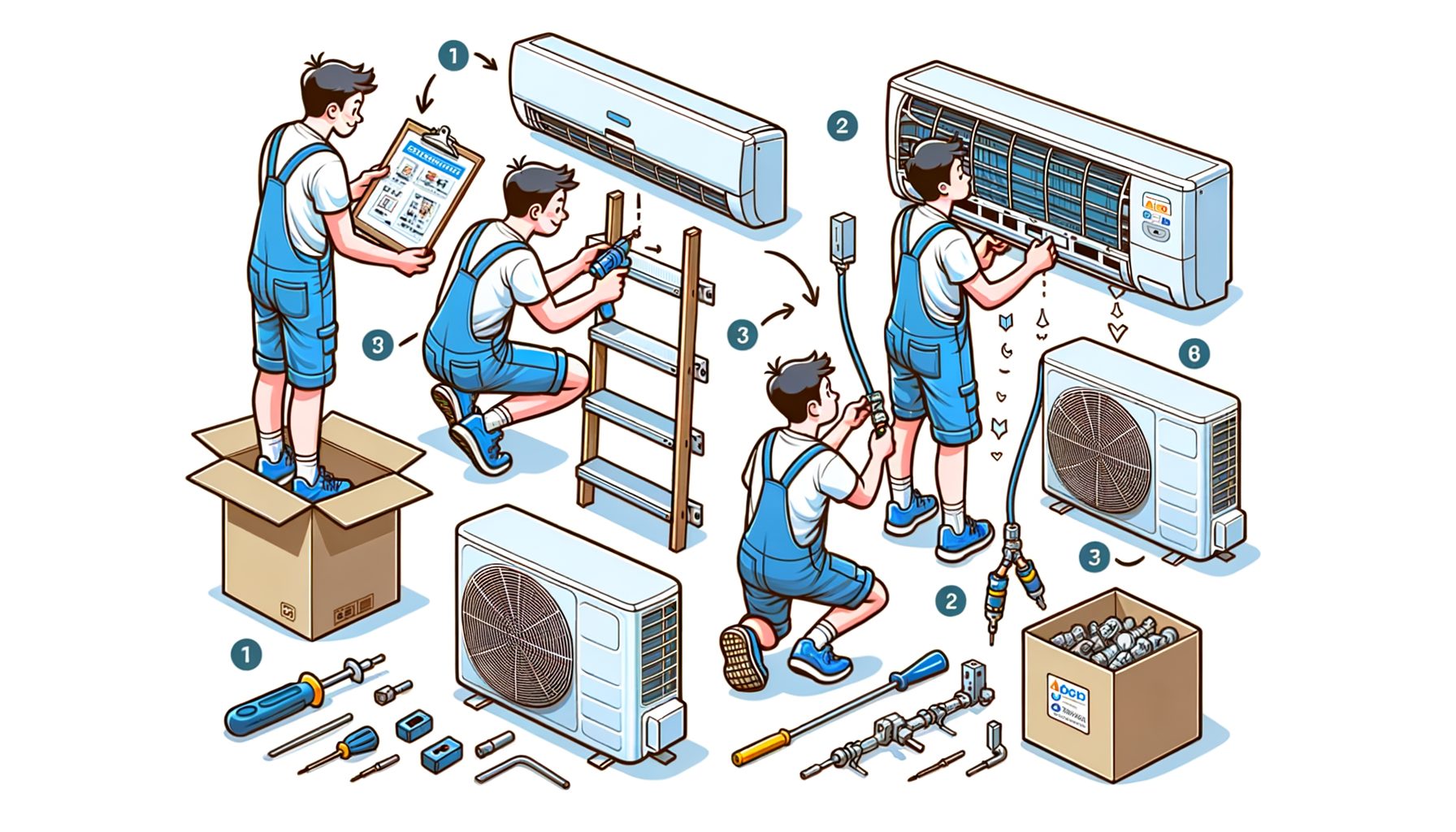

Split the project into two phases—“safe DIY” and “pro-required”—and your odds improve. Safe DIY typically includes: planning, choosing the right capacity and efficiency, selecting the mount location, installing the indoor bracket, drilling the wall hole, installing the wall sleeve, setting the outdoor pad or wall stand, routing the line set (without opening it), running the condensate drain with continuous downward pitch, and neatly pulling control cables through conduit where required by local code. Many DIYers also handle weatherproofing, such as sealing the exterior penetration with UV-stable sealant and insulating the line set with closed-cell foam and a protective wrap.

On the professional side, bring in a licensed electrician to add a dedicated circuit, breaker, and outdoor disconnect sized per your unit’s nameplate and local electrical code (for example, NFPA 70/NEC in the U.S.). A licensed HVAC tech should evacuate the lines, verify proper micron levels with a vacuum gauge, open service valves, weigh in any additional refrigerant if line length exceeds the factory charge, and confirm superheat/subcool targets. Prefer a fully DIY path without refrigerant handling? Consider “pre‑charged, quick‑connect” mini‑splits specifically designed for homeowners, such as MRCOOL DIY units, which include sealed line sets and do not require a vacuum pump. Always read the manufacturer’s manual and warranty terms; most brands clearly list which steps must be completed by a certified pro to maintain coverage.

Plan Like a Pro: Sizing, Placement, Tools, and Permits

Good planning prevents callbacks—especially when you are your own installer. Start with right-sizing. Oversized units short cycle, waste energy, and can leave rooms clammy. Undersized units run constantly and still feel warm. Use a load calculation, not guesswork. For a professional-grade result, ask a contractor for an ACCA Manual J calculation, or use a reputable online calculator that factors in climate zone, insulation, window area, and occupancy. As a quick reference, the table below shows typical room sizes and cooling capacities with an estimate of input power at SEER 20 (actual power varies):

| Room size | Approx. capacity | Capacity (kW) | Est. input at SEER 20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10–15 m² (100–160 ft²) | 9,000 BTU/h | 2.6 kW | ≈450 W |

| 15–25 m² (160–270 ft²) | 12,000 BTU/h | 3.5 kW | ≈600 W |

| 25–35 m² (270–375 ft²) | 18,000 BTU/h | 5.3 kW | ≈900 W |

| 35–50 m² (375–540 ft²) | 24,000 BTU/h | 7.0 kW | ≈1,200 W |

Placement comes next. The indoor head should throw air across the room, not directly at seating or beds. Keep at least the manufacturer’s clearance above and around the unit (usually 15–30 cm/6–12 inches above the top). Avoid mounting over electronics or shelves that could block airflow. The outdoor unit needs unobstructed intake and exhaust, typically 30–60 cm (12–24 inches) of free space on sides and back, and clear discharge in front. Direct sun and debris reduce performance; a shade canopy with open sides and a raised, level pad or wall brackets help extend life. In snowy climates, lift the condenser above snow height; in coastal areas, use corrosion-resistant hardware.

Before you buy, verify power requirements. Many 9k–12k BTU mini‑splits run on 120V or 230V; larger units are usually 230V. Check the nameplate for minimum circuit ampacity (MCA) and maximum overcurrent protection (MOCP) to size the breaker and wire gauge correctly. Plan for a weatherproof disconnect within sight of the outdoor unit, per local code. Confirm whether permits are required; many jurisdictions need electrical and mechanical permits for fixed equipment. For energy success and rebates, look for high-SEER, inverter-driven models; see the U.S. Department of Energy’s overview of ductless systems for efficiency insights.

Gather tools and materials early. Common items include a stud finder, level, hammer drill and core bit (65–80 mm/2.5–3.25 inches), wall sleeve, lag bolts, torque wrench (for flare nuts if applicable), line set cover, UV-rated sealant, condensate tubing, hose clamps, and PPE (gloves, safety glasses, hearing protection). If you are not using a pre‑charged quick‑connect system, your HVAC pro will need a vacuum pump, micron gauge, manifold set, and a nitrogen tank for pressure testing. Planning each step on paper—measurements, bends, drip loop, line lengths—prevents on-the-day surprises.

Step-by-Step Mounting and Routing: Indoor Unit, Condensate, Line Set, and Outdoor Placement

1) Mount the indoor bracket. Use a level and locate studs or solid masonry. The bracket must be dead level to keep condensate flowing to the drain side and to prevent vibration. Leave the manufacturer’s specified clearance on all sides. Before drilling, mark the wall core hole location; it should align with the unit’s service port and exit with a slight downward slope to the outdoors (about 5–10 mm per 300 mm, or 1/4 inch per foot) for proper drainage.

2) Drill the wall core and install the sleeve. A clean hole reduces line damage and air leakage. Insert the plastic or metal sleeve to protect insulation, wiring, and tubing. In climates with strong wind or pests, add a screened exterior termination cap. Seal around the sleeve later from both sides with a UV-stable, flexible sealant, but do not block the drain path.

3) Prepare and route the condensate drain. The drain is the most common source of callbacks. Keep a continuous downward pitch to the outside or to a trapped connection in a suitable drain. Avoid sags where algae can grow. In cold regions, insulate the drain or route it indoors to prevent freezing. If gravity cannot work, use a manufacturer-approved condensate pump and follow the pump’s installation instructions, including a service loop and check valve orientation.

4) Handle the line set carefully. If your system uses pre-flared, pre‑charged quick‑connect lines, follow the manufacturer’s torque specifications and cleanliness requirements. For standard systems, do not remove the caps or expose copper tubing to air until a professional is ready to connect, pressure test with nitrogen, and pull a vacuum. Kinks ruin line sets; make large, gentle bends using a bending spring or bender. Keep the suction line insulation intact and re-wrap any disturbed sections with UV-rated tape or line-hide covers for protection and a clean look.

5) Hang the indoor unit. Pull the line set, drain, and control wire through the sleeve gently. Latch the indoor unit onto the bracket. Ensure the drain stub is fully seated with the drain hose and clamp. Verify that the unit is still level front-to-back, with a slight manufacturer-recommended tilt if specified for drainage. Tug-test the connections lightly to confirm nothing is strained.

6) Set the outdoor unit. Place it on a level pad or secure wall brackets that can handle the weight plus vibration. Use anti-vibration pads or isolators to reduce noise transfer. Maintain clearances and orient the discharge away from walls, fences, or neighboring windows. Provide a drip path for defrost water if it is a heat pump. Route the line set to the service valves with minimal length and fewest bends to reduce pressure drop. Protect the penetrations and vertical runs with line set covers; they reduce UV damage and look tidy.

7) Weather-seal and finish. Seal around penetrations, add a downward-facing drip loop to outdoor cables, and keep all fasteners stainless or galvanized in corrosive environments. Label the disconnect and note the model, serial number, and installation date for future service records. At this point, all physical mounting and routing are complete; stop before opening the refrigeration circuit unless you are using a DIY quick‑connect system designed for homeowner installation.

Electrical, Refrigerant, and First Startup: Safe Commissioning and Early Maintenance Tips

Electric power is not the place to guess. Have a licensed electrician run a dedicated circuit from your panel to the outdoor disconnect, size the breaker and wire per the unit’s MCA and MOCP, and bond and ground per local code. Many mini‑splits receive their power at the outdoor unit, with a low-voltage or proprietary communication cable running to the indoor head(s). Follow the wiring diagram in your install manual exactly, paying attention to polarity and terminal labels. Poor or reversed wiring can damage circuit boards instantly. If your jurisdiction requires conduit or specific cable types (for example, UV-rated cable outdoors), comply fully.

For refrigerant work on conventional systems, hire a licensed HVAC technician. They will connect nitrogen to pressure test for leaks, pull a deep vacuum (often to 500 microns or below) and verify that the system holds vacuum without decay, then open the service valves to release the factory charge. If your line set length exceeds the factory-charged allowance, the tech will weigh in additional refrigerant. Done correctly, the process ensures moisture and non-condensables do not remain in the system—a leading cause of premature compressor failure. If you opted for a pre‑charged quick‑connect product designed for DIY, follow the manufacturer’s torque and valve-opening steps carefully, keep connections clean, and do not overtighten. Check all joints with a bubble solution to spot leaks before finishing covers.

Initial startup is about verification. After power-up, set the system to cool and observe: the indoor fan should start, then the outdoor unit should ramp up. Within 10–15 minutes, you should measure a temperature drop of roughly 8–12°C (15–22°F) between return and supply in cooling mode under typical indoor conditions. Listen for unusual vibration, rattles, or gurgling from the drain. Confirm that condensate is dripping outdoors or into a drain—not on your wall. Use the installer menu or app to set region, Wi‑Fi, and any advanced features like quiet mode or temperature compensation. If you have a heat pump, test heating as well to ensure reversing operation is smooth.

Early maintenance starts on day one. Clean the indoor air filters monthly during heavy use and rinse the coil surface gently if dust accumulates. Keep vegetation 60 cm (2 ft) away from the outdoor unit and hose off debris on the coil (power off first). Annually, inspect line set insulation for UV damage and check the drain for algae. These small steps preserve efficiency; according to the IEA, better cooling efficiency can dramatically cut global electricity demand, and simple maintenance is an easy win in that direction.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it legal to install a split AC myself?

In many places you may mount equipment and route drains and cables yourself, but electrical and refrigerant handling are regulated. In the U.S., only EPA Section 608–certified technicians can open or charge most refrigerant systems. Local permits and inspections may also be required. Check your local rules and your manufacturer’s warranty; some allow homeowner installation only when using specific DIY quick‑connect models.

Do I need a vacuum pump for installation?

For conventional mini‑splits with standard flare connections, yes—a vacuum pump and micron gauge are required to remove air and moisture before opening the service valves. Skipping that step will shorten equipment life. The exception is DIY-focused, pre‑charged systems with sealed quick‑connect lines; those are designed to avoid vacuum pumping when installed per instructions.

How long does the installation take?

For a first-time DIYer handling mounting, routing, and weatherproofing, plan a full day (6–10 hours) for a single‑zone system, not counting the electrician and HVAC technician visits. With experience, simple installs can be done in 3–5 hours. Complex routing, masonry walls, or long line runs add time.

What breaker size and wire gauge should I use?

Always size by the unit’s nameplate. Look for MCA (minimum circuit ampacity) and MOCP (maximum overcurrent protection). A licensed electrician will choose the breaker and conductor size that meets those values and local code (for example, NEC in the U.S.), considering run length and derating. Do not guess or copy another model’s sizes.

How do I prevent leaks and water damage?

Keep the indoor unit perfectly level, maintain continuous downward slope on the condensate line, secure the drain with a proper clamp, and test drainage by pouring a small cup of water into the drain pan before startup. Insulate the suction line fully to prevent condensation and wrap exterior penetrations with UV-stable sealant.

Conclusion: Your Next Steps to a Cooler, Safer, and More Efficient Home

Here’s the recap: you learned how to plan capacity and placement, what tasks you can safely handle yourself, and where to bring in licensed professionals to ensure code compliance, performance, and warranty protection. You also saw a realistic sequence for mounting the indoor and outdoor units, routing the line set and drain, sealing penetrations, and commissioning the system without common pitfalls. Whether you choose a conventional mini‑split with pro commissioning or a pre‑charged DIY kit, the path to install a split air conditioner safely is clear—plan carefully, follow the manual, respect local regulations, and verify each step.

Ready to act? Start by measuring your room, shortlisting two or three high‑efficiency inverter models, and calling a local electrician to confirm power requirements and costs. In parallel, schedule an HVAC technician for vacuum and startup, or, if you are going the quick‑connect route, confirm the model’s DIY eligibility and warranty terms. Take photos during installation and keep a simple log of measurements, torque values, and test results; that “owner’s record” makes future service faster and protects you if you ever need warranty support. Finally, set calendar reminders for filter rinses and a seasonal outdoor coil rinse; small habits can preserve efficiency and comfort for years.

Cooling is not just about comfort; it is about health, productivity, and resilience in hotter summers. With the right prep and respect for safety boundaries, your project can be cost‑effective, code‑compliant, and climate‑friendly. Ready to map your install? Pick your room, pick your unit, and plan your pathway today. The best time to build comfort is before the next heat wave hits—what will you upgrade first?

Helpful outbound resources:

U.S. DOE Energy Saver: Ductless Mini‑Split Heat Pumps

U.S. EPA Section 608 Refrigerant Management

ACCA Manual J (Residential Load Calculation)

NFPA 70 (National Electrical Code) Overview

MRCOOL DIY Pre‑Charged Mini‑Splits

Mitsubishi Electric Install Resources

Sources:

U.S. Department of Energy. Ductless Mini‑Split Heat Pumps. https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/ductless-mini-split-heat-pumps

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Section 608 Technician Certification. https://www.epa.gov/section608

Air Conditioning Contractors of America (ACCA). Technical Manuals (Manual J). https://www.acca.org/standards/technical-manuals

National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 70 (NEC) Overview. https://www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards/all-codes-and-standards/list-of-codes-and-standards/detail?code=70

International Energy Agency. The Future of Cooling. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-cooling

World Health Organization. Heatwaves. https://www.who.int/health-topics/heatwaves